When a patient in Germany, Spain, or Poland picks up a generic version of a blood pressure pill, they’re not just getting a cheaper version of the brand-name drug-they’re benefiting from a complex, multi-layered regulatory system that’s been redesigned in 2025 to speed up access, reduce delays, and keep prices low. But behind that simple pharmacy transaction lies a web of approval pathways, national differences, and new rules that determine exactly when-and if-that generic becomes available.

Four Paths to Market: How Generics Get Approved in the EU

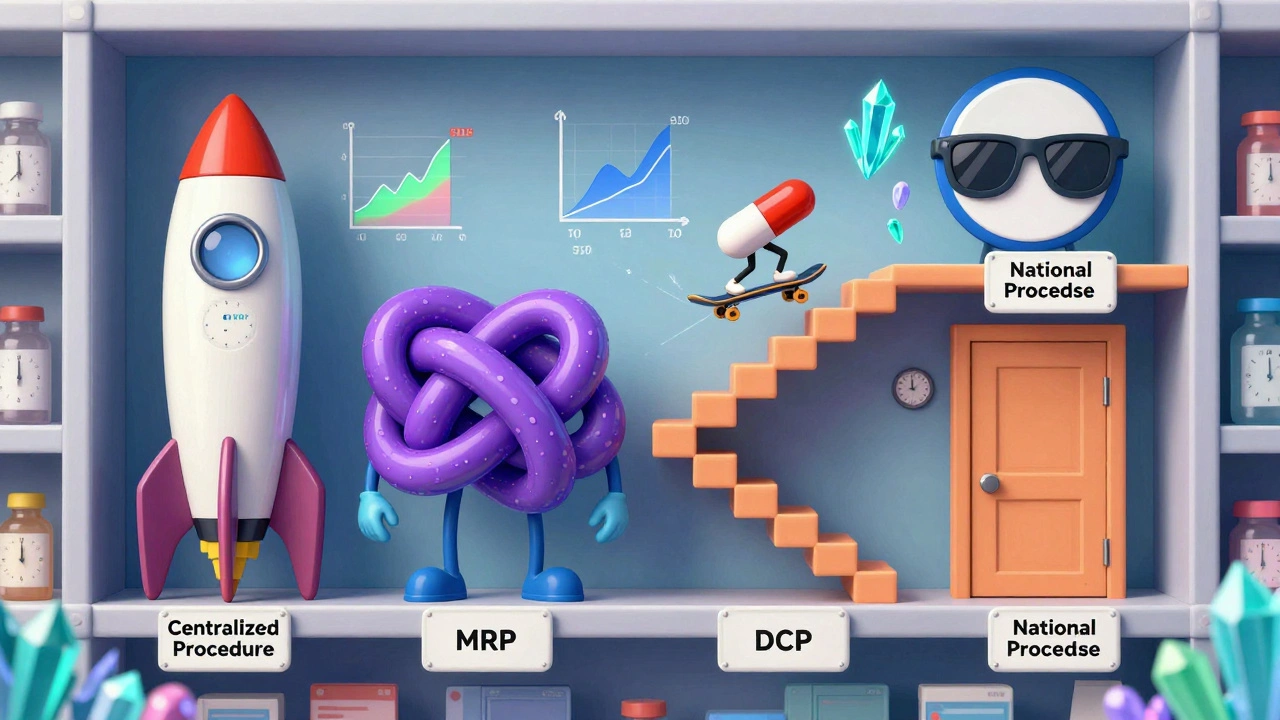

There’s no single way to get a generic medicine approved across the European Union. Instead, manufacturers must choose from four different routes, each with its own timeline, cost, and challenges. The choice isn’t just logistical-it’s strategic and can mean the difference between launching a product six months ahead of competitors or being stuck in regulatory limbo for over a year.

The Centralized Procedure is the fastest route to EU-wide access. A single application goes to the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and if approved, the generic can be sold in all 27 EU countries plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway. This path takes about 180 days under the 2025 reforms-down from 210-and gives manufacturers instant access to 30 markets. But it’s expensive: application fees start at €425,000, and consulting costs can push total spending to €1.2-1.8 million. Only high-value generics with projected sales over €250 million annually make sense here. Sandoz used this route for its version of Cosentyx, launching simultaneously across Europe in Q2 2025-11 months faster than traditional methods.

The Mutual Recognition Procedure (MRP) is the most commonly used, accounting for 42% of applications. A company gets approval in one country (the Reference Member State), then asks others to recognize it. Sounds simple, right? In practice, it’s messy. While the official timeline is 90 days, the average takes 132.7 days because countries add their own requirements. Teva’s 2023 launch of generic rosuvastatin hit a wall when Germany delayed pricing talks, which held up market entry in the Netherlands and Belgium by over eight months.

The Decentralized Procedure (DCP) lets companies apply to multiple countries at once without prior approval. It’s meant to be efficient, but it’s the most error-prone. One in three applications face delays longer than six months, especially when Eastern European regulators interpret quality standards differently. A 2024 GMDP Academy case study found inconsistent requirements for impurity levels and stability testing were the biggest bottlenecks.

The National Procedure is the least popular-used for only 5% of applications. It’s for companies targeting one specific market, like France or Italy, where reimbursement rules are especially favorable. But it’s slow (180-240 days) and offers no cross-border advantage. Accord Healthcare found it took 197 days to get a national approval in France, while using MRP for five countries took just 142 days.

What Makes a Generic ‘Equivalent’? The Science Behind Approval

Generics aren’t just copies. They must be identical in active ingredients, dosage form, and strength-and proven to work the same way in the body. The EMA’s Guideline on the Investigation of Bioequivalence sets the gold standard: bioequivalence studies must show that the generic’s absorption rate (Cmax) and total exposure (AUC) fall within 80.00-125.00% of the brand-name drug, with 90% confidence.

But what’s ‘identical’ isn’t always straightforward. For complex generics-like inhalers, injectables, or topical creams-additional testing is required. Germany’s BfArM demands extra pharmacodynamic studies for inhalers that other countries don’t. France requires pediatric formulation data even when the original product wasn’t designed for children. These national quirks force manufacturers to tailor submissions for each market, increasing costs and delays.

Even something as simple as polymorphic forms of a drug can trigger objections. German regulators require extra stability data if the generic uses a different crystal structure than the original. That’s not a safety issue-it’s a technical one. But under the old rules, it was enough to delay approval for months. The 2025 reforms didn’t fix this. They just made it clearer that companies need to anticipate these differences upfront.

The 2025 Pharma Package: How New Rules Are Changing the Game

On June 4, 2025, the EU finalized its biggest overhaul of generic medicine rules in 20 years. The Pharma Package didn’t just tweak a few forms-it rewrote the playbook for how generics enter the market.

The most impactful change? The expanded Bolar exemption. Before 2025, generic makers could only start pricing and reimbursement negotiations two months before a patent expired. Now, they can start six months earlier. That’s not just a calendar shift-it’s a strategic advantage. REMAP Consulting estimates this will cut average launch delays by 4.3 months. Payers get more time to compare prices. Manufacturers can line up supply chains earlier. And competitors can’t wait until the last minute to react.

Another key change: Regulatory Data Protection is now standardized at 8 years of data exclusivity plus 1 year of market protection (8+1). It can be extended to 10 years if the drug meets public health goals, like treating rare diseases. This reduces the total protection period from 10 years to 9 years for most drugs, giving generics a clearer path to market. But critics warn that the €490 million sales threshold for Transferable Exclusivity Vouchers-new incentives for companies developing drugs for underserved areas-could lock out mid-sized firms who can’t afford the lobbying or legal costs to compete.

And then there’s the obligation to supply. For the first time, manufacturers must prove they can keep producing enough generics to meet demand. National authorities can now demand proof of manufacturing capacity, backup suppliers, and quality control systems. It’s meant to prevent shortages, but Professor Panos Kanavos of LSE Health warns that vague definitions of ‘sufficient quantities’ could let countries quietly block entry by demanding unrealistic production volumes.

Who’s Winning? Market Players and Global Shifts

The EU generic market was worth €42.7 billion in 2024, growing 6.2% from the year before. But the winners aren’t evenly distributed.

Indian manufacturers now hold 38% of all EU generic approvals-up from 29% in 2020. Companies like Dr. Reddy’s, Cipla, and Sun Pharma have built scalable, low-cost operations that thrive under the DCP and MRP systems. They’re not chasing the expensive Centralized Procedure-they’re targeting high-volume, low-margin drugs where speed and price matter more than EU-wide branding.

European firms like Sandoz and Viatris still lead in market share at 52%, but their edge comes from strategic use of the Centralized Procedure. They focus on high-value generics-like those for autoimmune or cancer treatments-where simultaneous EU launch justifies the €1.5 million price tag. They also invest heavily in regulatory teams that understand both EMA standards and national quirks.

Eastern Europe is the fastest-growing region, with generics sales rising 9.8% annually. Countries like Poland and Romania are becoming manufacturing hubs-not just for their lower labor costs, but because their regulators are more flexible in interpreting bioequivalence data. This has created a two-tiered system: Western Europe gets complex, high-margin generics, while Eastern Europe handles volume-driven, low-cost products.

What’s Next? The Hidden Costs and Coming Challenges

Even with the 2025 reforms, the system isn’t smooth. Manufacturers are still wrestling with three big problems.

First, electronic documentation. By 2026, all product information must be submitted in XML format as electronic Product Information (ePI). That’s not just a file format change-it requires new IT systems. White & Case estimates this will cost companies €180,000-250,000 each to upgrade. Smaller firms may not survive the transition.

Second, inconsistent national guidance. A 2025 industry survey found 58% of companies received conflicting answers from national authorities compared to EMA guidelines. One company reported being told by France to use a different impurity profile than what EMA approved-forcing them to retest and resubmit.

Third, the Critical Medicines Act. Passed in March 2025, it requires stockpiling of 200 essential generics. Sounds good for patient safety-but it adds new layers of quality verification. Manufacturers now need to prove they can store, track, and rotate stock for years without degradation. That’s a new cost, a new audit, and a new barrier to entry.

The biggest question now is whether these reforms will actually reduce the 22.4-month gap between U.S. and EU generic launches. The U.S. gets generics in 8.7 months on average after patent expiry. Canada? 8.7 months. The EU? Still 22.4. The 2025 changes are a step forward, but they won’t close that gap overnight.

What Generic Manufacturers Need to Know Today

If you’re a generic manufacturer, here’s what matters right now:

- Choose your pathway based on volume and value. Use the Centralized Procedure only if you’re targeting high-value drugs. Otherwise, MRP is your best bet for multiple markets.

- Start bioequivalence studies 15-18 months before launch. The 2025 guidelines require more precise testing-don’t rely on old protocols.

- Build relationships with national regulators early. Don’t wait until submission. Ask questions about local requirements for polymorphs, impurities, or pediatric labeling.

- Prepare for ePI. If you haven’t started upgrading your IT systems, you’re already behind.

- Track the July 1, 2026 deadline for the new 8+1 data protection rule. It will unlock dozens of high-value generics currently blocked by patent extensions.

There’s no perfect system. The EU’s approach balances innovation with access, but the cost of that balance is complexity. The companies that win aren’t the ones with the biggest budgets-they’re the ones who understand the rules, anticipate the delays, and plan for the next reform before it even happens.

Comments

Christian Landry

December 8, 2025 AT 09:19 AMbro the ePI thing is gonna kill small pharma firms 😭 like, €250k to upgrade systems? no way. we’re talking about companies with 10 people and a shared google drive. this isn’t innovation, it’s a tax on being small.

Tejas Bubane

December 10, 2025 AT 09:03 AMIndian companies dominate EU generics now? lol. they don’t care about quality, just volume. i’ve seen batches from Cipla that looked like they were made in a garage with a 1998 centrifuge. EMA should’ve kept the standards tighter.

Guylaine Lapointe

December 11, 2025 AT 01:54 AMLet me get this straight - we’re celebrating ‘faster access’ while ignoring that national regulators are still throwing up roadblocks like drunk bouncers? The 2025 reforms are a PR stunt. If you think ‘8+1’ is meaningful, you’ve never read the fine print where ‘public health goals’ are defined by lobbyists with private jets.

Maria Elisha

December 12, 2025 AT 06:07 AMso basically the eu just made the system more complicated but called it ‘reform’? thanks for nothing. i just want my blood pressure med to be cheap and available, not a 12-page compliance form.

Katie Harrison

December 12, 2025 AT 20:52 PMAs someone who’s worked with regulatory teams across the EU, I’ve seen how national quirks aren’t just bureaucracy - they’re cultural. Germany’s obsession with crystal forms? It’s not about safety, it’s about legacy standards. France’s pediatric data demand? It’s precautionary, not illogical. The system isn’t broken - it’s just deeply, frustratingly human.

Mona Schmidt

December 14, 2025 AT 06:04 AMThe bioequivalence window of 80–125% is still wildly permissive. For drugs with narrow therapeutic indices - like warfarin or levothyroxine - that’s not ‘equivalent,’ it’s a gamble. Why are we still using a 1980s standard for 2025 medicine? We have better analytical tools now. We should be requiring within 90–110% for high-risk generics. The EMA’s guidelines are dangerously outdated.

And the Bolar exemption? Great, but only if payers actually use the extra six months. In reality, most reimbursement agencies delay approval until the last possible day anyway. The reform assumes rational actors - but healthcare systems aren’t rational. They’re bureaucratic, underfunded, and reactive.

Also, why is the Critical Medicines Act only about stockpiling? Why not mandate transparent pricing forecasts or require manufacturers to disclose production bottlenecks? We’re treating symptoms, not causes.

And the Indian manufacturers? Yes, they’re efficient - but their dominance reflects a race to the bottom. We’re importing low-cost generics while exporting our regulatory burden. The EU is becoming the world’s generic pharmacy - and we’re not even asking who’s paying the hidden costs.

The ePI transition? It’s not just about IT. It’s about data sovereignty. If every submission is XML, who owns that data? Who can audit it? Who’s liable if the format breaks during transfer? No one’s talking about this.

And the 8+1 rule? It sounds fair until you realize that ‘market protection’ is often extended via legal loopholes - like ‘new indications’ or ‘modified release forms’ - that aren’t truly innovative. We’re not reducing monopolies. We’re just rebranding them.

What’s missing is a centralized, open-access database of national regulatory decisions. If France rejects a polymorph, why can’t every manufacturer see why? Transparency isn’t a luxury - it’s the only way to reduce redundant testing.

And let’s not pretend the ‘two-tiered system’ is accidental. Western Europe gets the complex drugs. Eastern Europe gets the volume. That’s not efficiency - it’s economic colonialism dressed up as supply chain optimization.

The real win? Companies that treat regulatory strategy like product design - not a cost center. That’s the future. The rest? They’re just waiting for the next reform to bail them out.

Ajit Kumar Singh

December 15, 2025 AT 14:11 PMUS gets generics in 8 months EU 22 months? That’s not a gap that’s a crime. Why does it take longer to approve a pill than a new iPhone? The EMA is a paper-pushing machine with a 20-year-old software stack. Fix the system or shut it down.

Angela R. Cartes

December 16, 2025 AT 03:50 AMUgh. Another ‘deep dive’ that makes me want to throw my phone out the window. Can we just have cheap meds without 12 charts and 50 acronyms? 😩

Elliot Barrett

December 17, 2025 AT 23:45 PMIndian firms dominate? Of course they do - because they don’t waste money on over-engineered compliance. The EU’s system isn’t about patient access - it’s about protecting European pharma’s profits. The 2025 reforms? Just a fancy name for ‘more paperwork, same delays.’