What Is Retinal Vein Occlusion?

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) happens when a vein in the retina gets blocked, stopping blood from flowing out. This causes fluid and blood to leak into the retina, leading to swelling and vision loss. It’s not painful, but it can hit suddenly - one day your vision is fine, the next it’s blurry or dark in part of your eye.

There are two main types: central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO), which blocks the main vein, and branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO), which affects smaller branches. CRVO is more serious and often leads to worse vision loss. BRVO tends to affect only part of your vision, like the top or bottom half of your visual field.

It’s not rare. Around 16.4 million people worldwide have it, and most are over 55. But it can happen to younger people too - about 1 in 10 cases are under 45. The retina doesn’t heal on its own, so without treatment, vision can keep getting worse.

What Causes Retinal Vein Occlusion?

The blockage usually comes from a clot, but that clot doesn’t just appear out of nowhere. It’s tied to what’s happening in your blood vessels and overall health.

The biggest risk factor is high blood pressure. Up to 73% of people over 50 with CRVO have uncontrolled hypertension. Even if you don’t feel sick, high pressure inside your blood vessels can damage the thin walls of the retinal veins. That makes them more likely to narrow or get blocked.

Diabetes is another major player. About 10% of RVO patients over 50 have diabetes. High blood sugar damages blood vessels over time, making them stiff and more prone to clots. People with diabetes also tend to have worse outcomes after RVO.

High cholesterol plays a role too. If your total cholesterol is above 6.5 mmol/L, your risk goes up. That’s because fatty deposits can build up in arteries, and when a hardened artery crosses over a vein in the eye, it can squeeze it shut - that’s how BRVO often starts.

Glaucoma increases risk as well. If pressure inside your eye is too high, it can compress the vein at the optic nerve. That’s why people with glaucoma need regular eye checks - RVO can sneak in unnoticed.

Lifestyle matters. Smoking doubles your risk. Being overweight or inactive adds to the strain on your circulation. And for women under 45, birth control pills are a known trigger - especially if they have other risk factors like high blood pressure or clotting disorders.

Less common but serious causes include blood disorders like polycythemia vera (too many red blood cells), multiple myeloma, or inherited clotting problems like factor V Leiden. These are rare, but if you get RVO under 45, your doctor will likely test for them.

How Do Injections Help?

Injecting medicine directly into the eye is now the standard treatment for RVO. Why? Because the main problem isn’t just the blockage - it’s the swelling in the center of the retina, called macular edema. That’s what blurs your vision.

The two main types of injections are anti-VEGF drugs and corticosteroids.

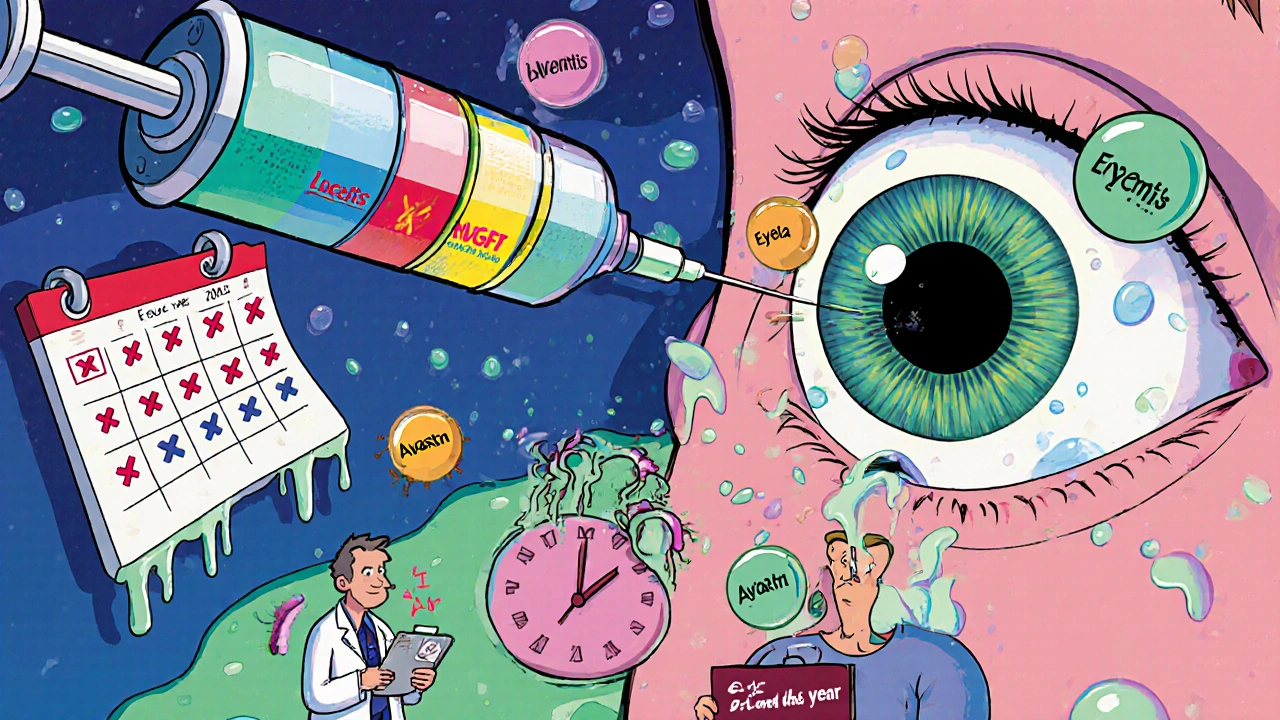

Anti-VEGF drugs like ranibizumab (Lucentis), aflibercept (Eylea), and bevacizumab (Avastin) block a protein called VEGF that causes blood vessels to leak. These injections reduce swelling and often improve vision. In clinical trials, people gained 15 to 20 letters on the eye chart - that’s like going from reading only the top line to reading most of the chart.

Corticosteroid injections, like the dexamethasone implant (Ozurdex), work differently. They reduce inflammation and swelling over a longer period. One implant can last 3 to 6 months. But they come with risks: they can cause cataracts or raise eye pressure, which might need extra treatment.

Doctors usually start with anti-VEGF because it’s safer long-term. Steroids are reserved for people who don’t respond well to anti-VEGF, or those with very severe swelling.

What’s the Treatment Process Like?

Getting an eye injection sounds scary, but it’s quick and routine. Most patients say the fear is worse than the procedure.

First, your eye is numbed with drops. Then the doctor cleans the surface with antiseptic and holds your eyelid open with a tiny clamp. The needle goes in through the white part of your eye - you might feel a little pressure, but not pain. The whole thing takes less than 10 minutes.

Afterward, you might see floaters or have a red spot on your eye. That’s normal. Serious complications like infection (endophthalmitis) happen in fewer than 1 in 1,000 injections.

Most people need injections every 4 to 6 weeks at first. After a few months, if the swelling improves, the schedule can stretch out. Some patients switch to a “treat-and-extend” plan - where they get injections spaced further apart as long as their vision stays stable.

Real-world data shows most people need 8 to 12 injections in the first year. That’s a lot, and it’s why many patients feel overwhelmed. But the payoff is real: 78% of people report major vision improvement after a year of treatment.

Costs and Accessibility

The price of these injections varies wildly. In the U.S., Lucentis and Eylea cost about $2,000 per shot. Avastin, which is used off-label, costs around $50. That’s why many hospitals and clinics use Avastin - it’s just as effective for many patients.

Insurance often covers the branded drugs, but copays can still hit $100-$150 per injection. For someone on a fixed income, that adds up fast. Some patients skip appointments because of cost, even though their vision is improving.

There’s also a new option coming: the Susvimo implant, which slowly releases medicine over months. It’s approved for another eye condition and is being tested for RVO. If it works, it could cut injections from monthly to quarterly - a game-changer for people tired of frequent visits.

What to Expect Long-Term

RVO isn’t cured by injections - it’s managed. Even if your vision improves, you’ll likely need ongoing monitoring. The blockage might heal, but the damage to your blood vessels doesn’t go away. That means you’re still at risk for new clots or swelling down the line.

Regular eye exams with OCT scans are key. These scans measure fluid thickness in the retina. If it goes above 300 micrometers, that’s a sign to restart treatment. If it drops below 250, you might be able to wait longer between injections.

Controlling your risk factors is just as important as the injections. Lowering blood pressure, managing diabetes, quitting smoking, and keeping cholesterol in check can prevent new problems in your eye - and your heart and brain too.

Emerging Treatments and Future Hope

Researchers are working on better ways to treat RVO. One promising area is gene therapy. The drug RGX-314 is being tested to deliver anti-VEGF genes directly into eye cells. If it works, you might only need one treatment that lasts years.

Another new drug, OPT-302, blocks a different VEGF protein and is being tested alongside aflibercept. Early results suggest it helps patients who didn’t respond well to standard treatment.

Doctors are also using advanced imaging to personalize care. Instead of treating everyone the same, they’re looking at patterns in blood flow and swelling to decide who needs steroids, who needs more frequent shots, and who might benefit from combo therapy.

The goal isn’t just to restore vision - it’s to reduce the burden. Fewer injections, fewer visits, fewer side effects. That’s the future.

What You Can Do Now

If you’ve been diagnosed with RVO, the most important thing is to stick with treatment. Vision can improve - even after months of blurry sight. But only if you keep going.

If you haven’t been diagnosed but are over 50 and have high blood pressure, diabetes, or high cholesterol, get your eyes checked yearly. RVO often has no warning signs until it’s too late.

And if you’re under 45 and had RVO? Ask your doctor about blood tests for clotting disorders. It’s rare, but knowing the cause can help prevent future issues.

There’s no magic pill. But with today’s treatments, most people with RVO can keep their vision - and their independence - for years to come.

Comments

Aishwarya Sivaraj

November 28, 2025 AT 10:19 AMI never thought about how much our eyes are connected to our heart health. After my mom had RVO, we found out her BP was through the roof and she didn't even know it. This post made me realize how much we ignore the quiet warnings our bodies give us. Just get your eyes checked if you're over 50. It's not scary, it's smart.

Also, Avastin being used off-label is wild but makes sense. Why pay $2000 when $50 does the same job? The system is broken but at least someone's fighting it.

Iives Perl

November 29, 2025 AT 21:36 PMThey're lying about the injections. The real reason they push these is because Big Pharma owns the eye clinics. You think they want you cured? No. They want you coming back every month. I've seen it. The 'treat-and-extend' plan? A trap. They're milking you. 🤡

steve stofelano, jr.

December 1, 2025 AT 20:30 PMThe clinical and empirical evidence presented in this exposition is both rigorous and profoundly illuminating. One cannot overstate the significance of early detection in retinal vascular pathology, particularly given the multifactorial etiological underpinnings. The integration of anti-VEGF therapeutics represents a paradigmatic shift in ophthalmic management, aligning with broader trends in precision medicine. One is compelled to commend the author for this lucid and comprehensive synthesis.

Savakrit Singh

December 3, 2025 AT 02:59 AMThis is why India needs better healthcare infrastructure. People here can't afford even $50 shots. And they don't even know what RVO is. My cousin got diagnosed late because she thought it was just 'eye strain'. Now she's blind in one eye. And doctors? They just hand out drops and send you away. 🤦♂️💉

Cecily Bogsprocket

December 3, 2025 AT 03:58 AMI know someone who went from barely seeing her grandkids to reading bedtime stories again after 10 injections. It's not easy. It's not quick. But it's worth it. I've sat in waiting rooms with people who were terrified of needles. They all said the same thing afterward: 'That was nothing.' You're stronger than you think. Keep going. Your vision matters. And so do you.

Emma louise

December 3, 2025 AT 08:32 AMSo let me get this straight. We're injecting drugs into our eyeballs because we won't stop eating donuts and smoking? Wow. What a brilliant healthcare system. We'd rather pump chemicals into people than tell them to eat a salad. Pathetic. 🙄

sharicka holloway

December 3, 2025 AT 14:18 PMI work with seniors who are scared of these injections. They think they're going to go blind from the needle. I just tell them: 'It's like a bee sting, and then you get to see your grandkids' faces again.' No one's ever regretted it. And if cost is the issue? Talk to your clinic. There are programs. You're not alone.

Shubham Semwal

December 5, 2025 AT 06:34 AMYou people are delusional. Anti-VEGF doesn't fix anything. It just delays the inevitable. The real problem is systemic inflammation from processed foods and sugar. No one wants to talk about that. They'd rather sell you a $2000 shot than admit the food industry is killing us. And don't even get me started on how birth control pills are a silent epidemic. Women are being poisoned and no one cares.

Sam HardcastleJIV

December 6, 2025 AT 07:39 AMOne must question the ethical implications of off-label drug use, particularly when financial incentives may unduly influence clinical decision-making. The disparity between branded and generic therapeutics, while economically rational, raises concerns regarding equity in access to standardized care. One is left to wonder whether patient outcomes are truly prioritized-or merely optimized for institutional efficiency.

Mira Adam

December 7, 2025 AT 03:39 AMYou think this is bad? Wait till you hear about the 200+ clinical trials that were buried because they showed steroids were better. The FDA is in bed with pharma. They don't want you to know that a cheap steroid implant could save you 10 shots a year. They want you dependent. And you're falling for it.

Miriam Lohrum

December 8, 2025 AT 11:39 AMIt's interesting how we treat the eye as separate from the body. But the retina is just a window into the vascular system. If your eye's veins are clogging, your heart and brain are probably whispering the same thing. We fix the symptom, not the story. Maybe we should be listening more.

Emma Dovener

December 8, 2025 AT 17:12 PMI'm a nurse in a rural clinic. We use Avastin because it's the only thing we can afford. The patients are grateful. The results are real. I've seen people go from reading nothing to reading their grandchildren's names. No one's perfect, but this works. And it's not magic-it's science. Don't let the noise drown out the hope.

Edward Batchelder

December 9, 2025 AT 16:33 PMI want to thank the author for this incredibly thoughtful and detailed breakdown. I've been managing RVO for my father for two years now, and this is the first time I've seen all the pieces laid out so clearly. The 'treat-and-extend' model made so much sense after reading this. We've gone from monthly visits to every 10 weeks. He's reading again. We're sleeping better. Thank you for not just giving facts-but giving hope.

Allison Turner

December 10, 2025 AT 15:27 PMAll this fancy talk and still people go blind. Why? Because they don't care. Doctors don't care. Insurance doesn't care. You're just a number. Get your eyes checked or don't. Who cares?