A sudden spike in blood pressure to 240/130 during what looks like a panic attack. Severe headaches that come and go without warning. Sweating so heavy it soaks your clothes in a cool room. These aren’t just stress symptoms-they could be signs of a rare adrenal tumor called pheochromocytoma.

What Exactly Is a Pheochromocytoma?

Pheochromocytoma is a tumor that grows in the adrenal medulla-the inner part of the adrenal glands, which sit on top of your kidneys. These glands normally produce hormones like adrenaline to help you respond to danger. But in pheochromocytoma, the tumor makes too much of these hormones-epinephrine and norepinephrine-on its own, even when there’s no threat.

This isn’t cancer in most cases. About 90% of these tumors are benign, meaning they don’t spread. But even non-cancerous ones can be dangerous because of the hormone surges. The tumor doesn’t grow fast, but the effects are explosive. Each hormone burst can cause a sudden, terrifying episode called a “pheo spell.”

These tumors are rare. Only 0.1% to 0.6% of people with high blood pressure have one. That means most doctors will see one or two cases in their entire career. That rarity is part of why they’re often missed.

Why Does It Cause High Blood Pressure?

Essential hypertension-high blood pressure with no clear cause-usually creeps up slowly. Your blood pressure stays elevated all day. Pheochromocytoma is different. It causes paroxysmal hypertension: sudden, violent spikes that can hit 180 mmHg or higher in systolic pressure.

These spikes aren’t random. They’re triggered by things like physical exertion, emotional stress, anesthesia, or even urinating (if the tumor is in the bladder wall). You might feel fine one minute, then suddenly your heart pounds, your vision blurs, your skin turns pale, and your blood pressure skyrockets.

What makes this even trickier is that some people also experience orthostatic hypotension-dizziness when standing up-because the body’s ability to regulate blood pressure gets messed up. So you might have both high and low pressure at different times, confusing doctors who expect one or the other.

Unlike other causes of secondary hypertension-like kidney artery blockage or excess aldosterone-pheochromocytoma comes with a classic trio: headaches, sweating, and rapid heartbeat. If you have all three, the chance of having this tumor jumps dramatically.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Diagnosis starts with blood and urine tests-not imaging. The gold standard is measuring metanephrines, which are breakdown products of adrenaline and noradrenaline. A 24-hour urine collection for fractionated metanephrines is 96-99% sensitive. Blood tests for plasma-free metanephrines are almost as accurate.

Here’s the catch: if your levels are only slightly above normal, you might be overdiagnosed. About 15-20% of borderline results turn out to be false positives. That’s why doctors don’t rush to scan you. They wait for clear biochemical proof first.

Once the hormone levels confirm the diagnosis, imaging follows. CT or MRI scans show the tumor’s size and location. Newer scans like 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT are more accurate, spotting tumors that older methods miss. About 10% of these tumors aren’t even in the adrenal glands-they’re elsewhere in the body, called paragangliomas.

Genetic testing is now standard for everyone diagnosed. Why? Because 35-40% of cases are linked to inherited mutations in genes like SDHB, SDHD, VHL, or RET. Even if no one in your family has had it, you could still carry the mutation. Finding it changes how you’re monitored for life.

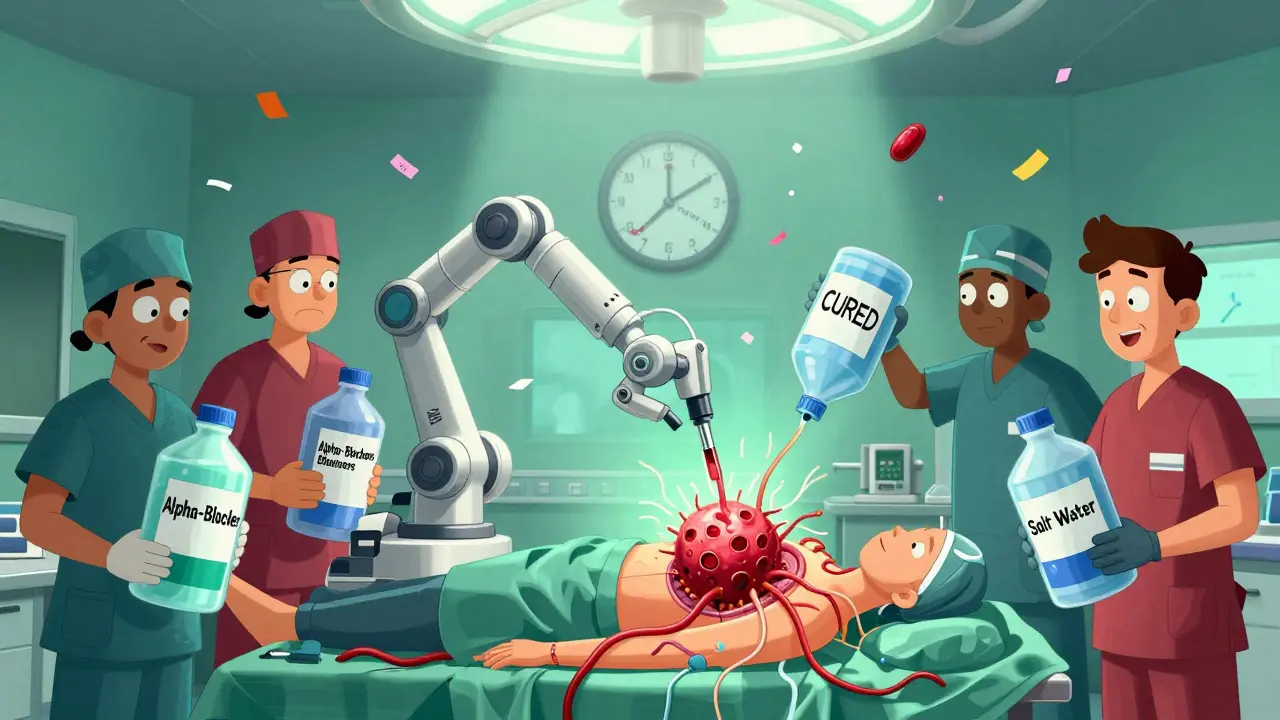

What Happens During Surgery?

Surgery is the only cure. Removing the tumor usually normalizes blood pressure. In 85-90% of cases, patients stop all blood pressure meds within weeks.

But surgery isn’t simple. You can’t just go under the knife. Preparing for it takes weeks. First, you start alpha-blockers like phenoxybenzamine. These drugs block the effects of excess adrenaline, preventing dangerous spikes during surgery. You take them for 7-14 days.

Then you increase your salt and fluid intake. The tumor causes your blood vessels to stay tight for months, shrinking your blood volume by 20-30%. Without extra fluids, your body can’t handle the drop in pressure when the tumor is removed. You might need 2-3 liters of water a day and over 200 milliequivalents of sodium.

Most surgeries today are laparoscopic-small cuts, camera, and tools. It’s minimally invasive. At high-volume centers, over 85% of unilateral cases are done this way. But if the tumor is large, stuck to nearby organs, or bleeds easily, the surgeon may need to switch to open surgery. That happens in 5-8% of cases.

Complications during surgery are rare if done right, but they’re deadly if not. Without proper blockade, a tumor can release a flood of adrenaline during removal, causing a hypertensive crisis. That can lead to stroke, heart attack, or death. That’s why experienced endocrine surgeons are essential.

What’s Recovery Like?

Most people leave the hospital in 1-2 days. Many return to work in two weeks. But recovery isn’t just about healing the incision.

If you had one adrenal removed, your other gland usually takes over. You might need temporary steroid support, but most don’t need it long-term.

If both glands are removed-which happens in 10% of cases, especially with hereditary syndromes-you’ll need lifelong hormone replacement: hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone. Without them, you risk adrenal crisis, which can be fatal.

Some patients report chronic fatigue for six months or more after surgery. It’s not well understood, but it’s common enough that support groups list it as a top concern.

What Happens After Surgery?

Even after successful removal, follow-up is critical. For benign, non-hereditary tumors, annual urine metanephrine tests are enough. But if you have an SDHB mutation, your risk of recurrence or metastasis is 30-50%. You need yearly whole-body MRIs for life.

Metastatic pheochromocytoma is rare but serious. Survival drops to about 50% at five years. New treatments like PRRT (peptide receptor radionuclide therapy) are showing promise, with 65% of patients seeing tumor shrinkage. Drugs like Belzutifan, originally for kidney cancer, are now being tested in VHL-related cases.

Genetic counseling is not optional. If you carry a mutation, your siblings and children should be tested. Early detection saves lives.

Why So Many Get Misdiagnosed

It’s not doctors being careless. It’s the symptoms mimicking far more common conditions. Panic attacks. Migraines. Menopause. Even anxiety disorders. In fact, 42% of patients are first treated for anxiety. One woman spent four years seeing seven doctors before her blood pressure spiked in the ER and someone finally ordered the right test.

When you’re young and healthy, doctors don’t think of rare tumors. They think of stress. But if your symptoms come in waves, if you’re sweating through a winter night, if your blood pressure jumps from normal to 200/120 without reason-don’t let them dismiss it.

Pheochromocytoma is curable. But only if it’s found. The average delay from first symptom to diagnosis is over three years. That’s three years of unnecessary stress, heart strain, and risk of stroke.

What You Should Do If You Suspect It

If you have recurring episodes of:

- Sudden, severe headaches

- Profuse sweating without heat or exertion

- Heart palpitations or racing pulse

- Episodes of high blood pressure that come and go

Ask your doctor for plasma-free metanephrines or a 24-hour urine metanephrine test. Don’t wait for a crisis. Don’t let them label it as anxiety. Push for the test. It’s simple, non-invasive, and life-saving.

If you’ve been told you have essential hypertension but your meds don’t seem to help, or your blood pressure fluctuates wildly, ask if pheochromocytoma has been ruled out. It’s not common-but it’s one of the few high blood pressure causes you can actually cure.

There’s no pill for this. No lifestyle change that fixes it. Only surgery. And when done right, it works.

Comments

Kaylee Esdale

December 18, 2025 AT 05:31 AMBeen there. Sweating through winter nights, heart racing like I’d run a marathon-no reason. Doctors called it anxiety for years. Then one ER doc ordered metanephrines. Turned out I had a tiny tumor on my left adrenal. Surgery in 6 weeks. Now I’m off all meds. Life’s quiet again. Don’t let them dismiss you.

Chris Van Horn

December 19, 2025 AT 20:30 PMIt is, of course, profoundly regrettably that the medical establishment continues to overlook this condition with such alarming frequency. The biochemical diagnostics are not only robust-they are unequivocally superior to the baseless psychologizing that dominates primary care. One must wonder whether the average physician has ever read a single peer-reviewed endocrinology paper.

Peter Ronai

December 20, 2025 AT 11:58 AMOh please. You think this is rare? I’ve seen five cases in my family alone. My uncle died from a hypertensive stroke because his doctor thought he was just 'stressed.' And now they want you to wait for a 24-hour urine test? That’s a death sentence. Get the PET scan first. Always. No excuses.

Anu radha

December 20, 2025 AT 23:02 PMThis made me cry. My sister went through this. Took 4 years. She’s fine now, but I wish someone had told us sooner. Thank you for writing this.

Sachin Bhorde

December 21, 2025 AT 06:03 AMBro, the metanephrine test is the key. Plasma free metanephrines > urine any day. And if you're from India, don't wait for fancy PET scans-get the basic blood test done at a good lab like SRL or Dr. Lal PathLabs. I’ve seen cases where the tumor was in the bladder wall-yes, really. SDHB mutations? Get genetic testing. Your kids need to know.

Joe Bartlett

December 21, 2025 AT 11:51 AMYup. Been in the NHS. Same story. Doctors think it’s panic attacks. Then someone finally orders the test. Boom. Tumor gone. Surgery done. Back to work. Simple. Why is this so hard?

Marie Mee

December 22, 2025 AT 20:50 PMThey’re hiding this on purpose. Big Pharma doesn’t want you cured. They make billions off blood pressure pills. This tumor? It’s a threat. That’s why they make you wait. They want you on meds forever. Watch your back.

Salome Perez

December 23, 2025 AT 11:56 AMAs someone who has worked in global health policy for over two decades, I find this exposition not only clinically precise but also culturally resonant. The diagnostic delay experienced across socioeconomic strata-particularly in low-resource settings-is a systemic failure that demands urgent structural intervention. The biochemical specificity of metanephrine assays, when paired with accessible genetic counseling, represents not merely a medical advance but a moral imperative.

Kent Peterson

December 24, 2025 AT 08:16 AMWait-so you’re telling me that a 0.6% prevalence rate is somehow ‘rare’? That’s like saying ‘a single lightning strike’ is rare. And you call this ‘curable’? What about the 10% who get metastatic disease? And you gloss over the fact that 40% of cases are genetic? This post is dangerously oversimplified. People need to know the truth-not a feel-good PSA.

Josh Potter

December 25, 2025 AT 21:22 PMBro I had this. Felt like I was dying every week. Then I found a doc who actually listened. Got the test. Surgery. Now I run marathons. Don’t wait. Don’t overthink. Just ask for the metanephrine test. Seriously. Do it.

Evelyn Vélez Mejía

December 25, 2025 AT 23:04 PMThere is a profound existential irony in the fact that a tumor, invisible and silent, can hijack the autonomic nervous system-the very mechanism meant to preserve life-and turn it into a weapon against its host. To suffer from pheochromocytoma is to be haunted by your own biology. And yet, the cure is surgical, mechanical, almost brutal in its simplicity. We do not heal through wisdom alone, but through the scalpel’s precision. Perhaps that is the most humbling truth of all.

Nishant Desae

December 27, 2025 AT 05:58 AMI work in a rural clinic in India, and we see a lot of people with high BP who get labeled as 'stress cases.' But when they come in with sweating, palpitations, and headaches that come in waves, we always check metanephrines. We don’t have PET scans, but the blood test works. One guy, 32, had a tumor the size of a lemon. After surgery, his BP went from 190/110 to 110/70. No meds. His wife cried. I cried. This isn’t just medicine-it’s second chances. Please, if you’re reading this and have these symptoms, don’t wait. Push. Even if they laugh.

BETH VON KAUFFMANN

December 28, 2025 AT 11:09 AMMetanephrines? Please. The sensitivity claims are inflated. Most labs don’t even follow pre-analytical protocols-no fasting, no supine position, no stress avoidance. You get false positives, then you get unnecessary surgeries. This whole thing is overdiagnosed. And the genetic testing? 35-40%? That’s cherry-picked data from tertiary centers. In the real world, it’s more like 10%. This post is a hype machine.

Sam Clark

December 29, 2025 AT 07:01 AMThank you for sharing this comprehensive and clinically accurate overview. For patients navigating this journey, I want to emphasize that while the diagnosis can feel isolating, there are robust support networks available-including the Pheo Para Alliance and international registries. Early detection is not only possible-it is within reach. Your advocacy, however small, can be the catalyst for another life saved.