Blood Sugar Unit Converter

Blood Sugar Unit Converter

When someone with diabetes slips into a severe hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia emergency, every minute counts. These aren’t just bad days-they’re life-threatening events that demand immediate, correct action. Too often, people wait too long, use the wrong treatment, or don’t know what to do at all. The difference between survival and tragedy comes down to knowing exactly what to do-and having the right tools ready.

What Counts as a Severe Emergency?

Severe hypoglycemia happens when blood sugar drops below 54 mg/dL (3.0 mmol/L), and the person can’t treat themselves. They might be confused, unconscious, or having seizures. This isn’t a case of feeling shaky or sweaty-it’s when the brain isn’t getting enough glucose to function. It most often occurs in people using insulin or certain oral medications like sulfonylureas. About 30% of people with type 1 diabetes experience at least one severe episode each year. Severe hyperglycemia isn’t just high blood sugar. It’s when the body starts breaking down fat for energy because it can’t use glucose, leading to dangerous acid buildup. This shows up in two forms: diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS). DKA usually happens in type 1 diabetes, with blood sugar over 250 mg/dL, ketones in the blood or urine, and blood pH below 7.3. HHS is more common in type 2 diabetes, with blood sugar often above 600 mg/dL, extreme dehydration, and no significant ketones. Both can lead to coma or death if untreated.Glucagon: The Lifesaver for Severe Hypoglycemia

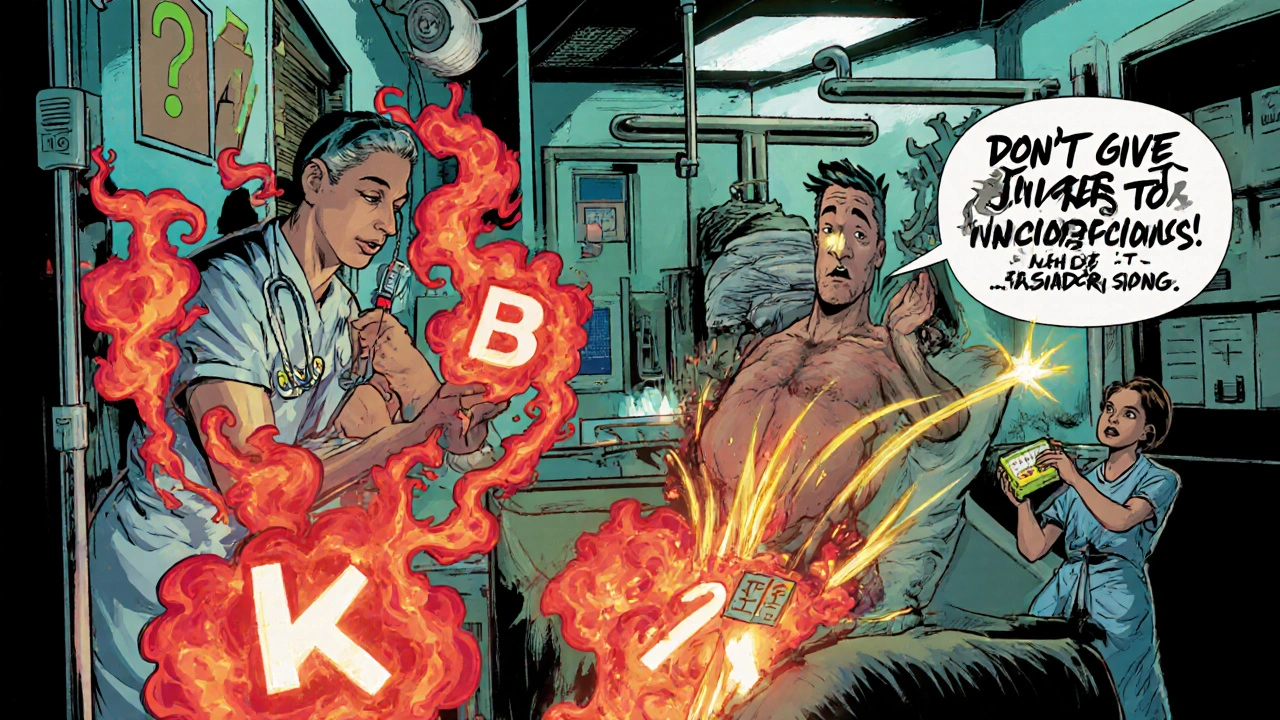

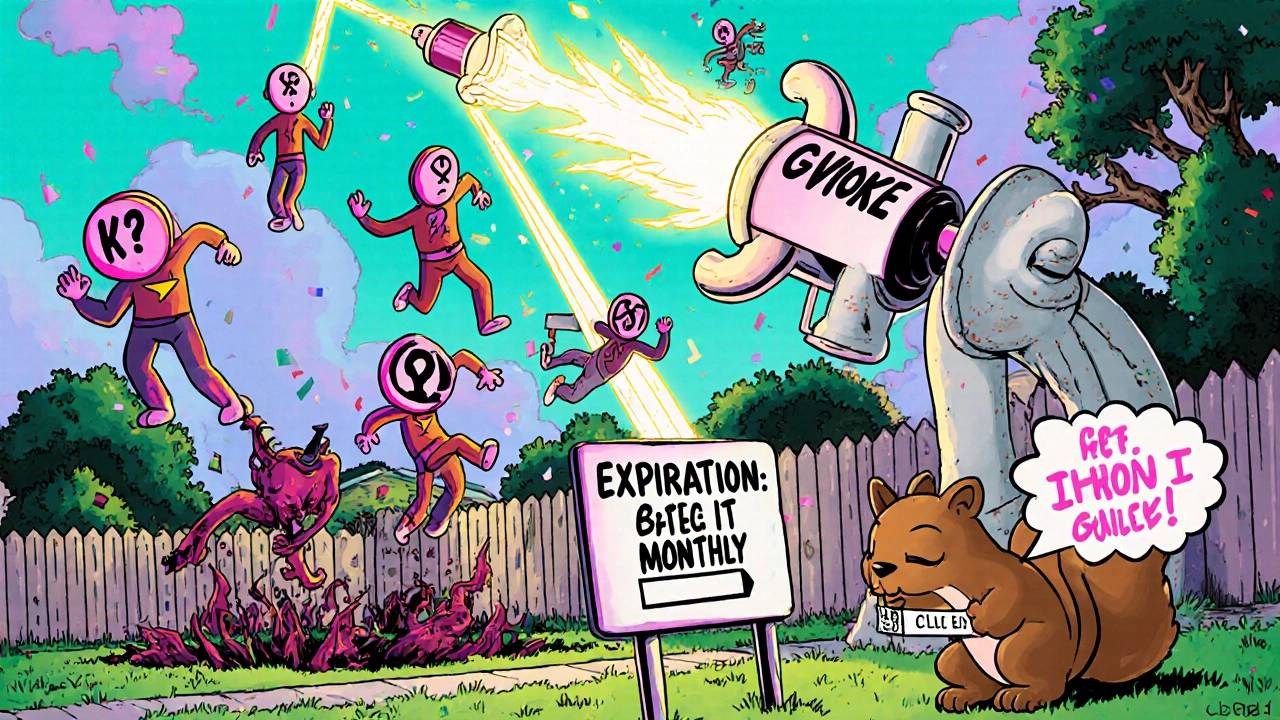

If someone is unconscious or unable to swallow, you don’t give them juice or candy. You give them glucagon. This hormone tells the liver to dump stored glucose into the bloodstream. For years, the only option was a tricky kit: mix powder with liquid, draw it up, and inject it. Most people never learned how. A 2021 study showed only 42% of caregivers could successfully use the old kit. Now, there are better options. Baqsimi is a nasal powder you simply spray into one nostril. Gvoke is a pre-filled autoinjector-you press it against the thigh or arm, hold for five seconds, and it’s done. Both work in under 15 minutes. In clinical trials, nasal glucagon raised blood sugar in 93% of cases. And the time to administer? Less than 30 seconds, compared to over two minutes for the old method. But here’s the hard truth: even though these tools exist, 59% of people at risk still don’t carry them. Fear of using them wrong is the top reason. Training helps. A 30-minute video tutorial boosts success rates from 32% to 89%. Families should practice with training devices every few months-skills fade fast without repetition.What NOT to Do During Hypoglycemia

Never try to give food or drink to an unconscious person. Choking or aspiration pneumonia can kill faster than low blood sugar. Don’t put anything in their mouth-not even water. Don’t shake them or slap their face. Don’t wait to call 911 if they don’t wake up after glucagon. Glucagon isn’t magic-it can take up to 20 minutes to work. If they’re still out after 15 minutes, call emergency services immediately. Also, don’t assume they’re just “sleeping it off.” A person with severe hypoglycemia may look like they’re passed out, but their brain is starving. This isn’t a hangover. It’s a medical emergency.Hyperglycemia Emergencies: It’s Not Just About Insulin

When blood sugar spikes above 250 mg/dL and ketones are present, this isn’t a missed dose-it’s a system failure. The body is burning fat, making acid, and losing fluids through urine. People often delay seeking help because they think, “I just need more insulin.” That’s dangerous. In the hospital, treatment is a three-step process: fluids, electrolytes, insulin. First, they give 1 to 2 liters of saline IV to rehydrate. Then, they replace potassium, which drops dangerously low as insulin starts working. Finally, they give insulin through an IV drip-not a shot. The dose is precise: 0.1 units per kilogram of body weight per hour. Too much insulin too fast can crash potassium levels, causing heart rhythm problems. For mild DKA (pH above 7.0), some doctors now use fast-acting insulin shots under the skin. But for severe cases or HHS, IV insulin is non-negotiable. And you must check ketones. A blood ketone level over 1.5 mmol/L means you’re heading into danger. Waiting until you’re vomiting or confused is too late.

Why Mixing Up Treatments Is Deadly

Giving glucagon to someone with hyperglycemia will make their blood sugar skyrocket. Giving insulin to someone with hypoglycemia will send them into a coma. These aren’t just mistakes-they’re fatal errors. Emergency responders and family members need clear protocols. If you don’t know the blood sugar level, don’t give anything. Wait for a meter reading. If you can’t test, assume it’s hypoglycemia and give glucagon. It’s safer than doing nothing. The FDA and American Diabetes Association now require all insulin prescriptions to come with glucagon. But access is unequal. Medicaid patients face prior authorization 31% of the time. Private insurance covers it 88% of the time. Black and Hispanic patients are 2.3 times more likely to be hospitalized for severe hypoglycemia-not because they’re less careful, but because they’re less likely to have glucagon in the house.What to Keep in Your Emergency Kit

Your emergency kit shouldn’t be hidden in a back cabinet. Keep it where everyone can find it: the kitchen counter, the car, the school nurse’s office. Here’s what it needs:- One ready-to-use glucagon (Baqsimi or Gvoke)-check the expiration date monthly

- Four glucose tablets (each 4g, total 15g) for mild lows

- A small bottle of regular soda (not diet) or juice box (15g carbs)

- A blood glucose meter with extra test strips

- A ketone meter or test strips (if you’re on insulin)

- A printed emergency plan with names, numbers, and instructions

New Tech Is Changing the Game

The first dual-hormone artificial pancreas, the Beta Bionics iLet, was approved in 2023. It automatically gives small doses of glucagon when it predicts a low. In trials, it cut severe hypoglycemia by 72%. But it’s only available at 12 U.S. centers right now. It’s expensive. Insurance coverage is limited. Meanwhile, apps like Eli Lilly’s Gvoke HelperApp walk you through administration step-by-step using your phone camera. It’s not a replacement for training-but it’s a safety net.

What You Can Do Today

1. Check your glucagon. Is it expired? Is it even in your house? If not, ask your doctor for a prescription for Baqsimi or Gvoke. 2. Teach someone. Show your partner, parent, coworker, or friend how to use it. Practice with the trainer device. 3. Know the signs. Confusion, slurred speech, seizures, or unconsciousness = call 911 and give glucagon. 4. Test for ketones. If your blood sugar is over 250 mg/dL and you feel nauseous or breath smells fruity, test for ketones. If it’s over 1.5 mmol/L, go to the ER. 5. Don’t wait. People wait 12 hours or more before seeking help for hyperglycemia. By then, it’s too late. Early action saves lives.When to Call 911

Call emergency services immediately if:- The person is unconscious or having seizures

- Glucagon was given but there’s no response after 15 minutes

- They’re breathing rapidly, vomiting, confused, or have fruity-smelling breath

- You suspect DKA or HHS, even if they’re still awake

Why This Matters More Than You Think

Untreated severe hypoglycemia kills 6% of people within 24 hours. Untreated DKA kills 70%. With proper care, those numbers drop to 1-5%. This isn’t about being “responsible.” It’s about survival. And it’s not just for people with type 1 diabetes. People with type 2 on insulin are just as vulnerable. Yet only 34% of them carry glucagon. The tools exist. The training is available. The knowledge is out there. What’s missing is action. Don’t wait for a crisis to learn what to do. Start today.Can you give glucagon to someone who’s awake but confused?

Yes. If someone is confused, disoriented, or unable to safely swallow, they need glucagon-even if they’re not unconscious. Confusion means their brain isn’t getting enough glucose. Giving them food or drink could cause choking. Glucagon is safe and fast-acting. Administer it immediately and call 911.

Is glucagon only for type 1 diabetes?

No. Anyone on insulin-whether type 1, type 2, or gestational diabetes-is at risk for severe hypoglycemia. People on sulfonylureas (like glipizide or glyburide) are also at risk. Glucagon should be available to anyone prescribed insulin, regardless of diabetes type.

Can you use glucagon if you don’t know the person’s blood sugar?

Yes. If someone is unconscious, having a seizure, or too confused to treat themselves, and you can’t check their blood sugar right away, give glucagon. It’s harmless if their sugar is normal-it won’t cause dangerous highs. But if their sugar is low and you wait, they could die. Glucagon is safer than doing nothing.

What should you do after giving glucagon?

Turn the person on their side to prevent choking if they vomit. Call 911. Once they’re awake and able to swallow, give them 15 grams of fast-acting carbs (like juice or glucose tablets), then a snack with protein and carbs (like peanut butter on bread). Monitor them closely for the next 2-4 hours. Glucagon causes a rebound high, so check blood sugar every 15-30 minutes.

Why do some people avoid carrying glucagon?

Fear is the biggest reason-fear of using it wrong, fear of causing a high, fear of embarrassment. Some think it’s only for “serious” cases. Others don’t realize how easy the new nasal and autoinjector forms are. Training and education reduce fear. Practice with a trainer device. Talk to your doctor. You’re not overreacting-you’re preparing.

Can you use an old glucagon kit if that’s all you have?

Yes. Even the old powder-and-syringe kits work. If it’s not expired, use it. Mix the powder and liquid quickly, inject into the thigh or arm, and call 911. It’s slower and harder to use-but it saves lives. Don’t let perfection stop you from acting. Any glucagon is better than none.

Are there side effects from glucagon?

Glucagon can cause nausea and vomiting in about 30% of people. It may also cause a temporary rise in blood pressure or heart rate. These are not dangerous in the context of a low blood sugar emergency. The risk of not using glucagon-death-is far greater. If vomiting happens, turn the person on their side.

Can SGLT2 inhibitors cause hyperglycemia emergencies?

Yes. Medications like canagliflozin and dapagliflozin (SGLT2 inhibitors) can cause euglycemic DKA-where blood sugar isn’t extremely high, but ketones are. This can happen during illness, surgery, or reduced food intake. If someone on these drugs feels sick, has nausea, or breathes fast, check ketones-even if their blood sugar is under 250 mg/dL.

What’s the difference between ketone strips and blood ketone meters?

Urine ketone strips show ketones from hours ago. Blood ketone meters show current levels. For emergencies, blood ketones are critical. A reading over 1.5 mmol/L means you’re in danger. Urine strips can be negative even when blood ketones are high, especially if the person is well-hydrated. Blood testing is faster and more accurate.

How can schools or workplaces prepare for these emergencies?

Every school or workplace with someone on insulin should have a written emergency plan, access to glucagon, and trained staff. The plan should include who will administer glucagon, where it’s stored, and how to call 911. Training should be hands-on with a trainer device. Don’t rely on the person’s parent or caregiver to always be there. Everyone needs to know what to do.

Comments

David vaughan

November 21, 2025 AT 14:30 PMJust got my Baqsimi prescription yesterday-finally! I’ve been scared to use the old kit for years… like, what if I mess up the mixing? 😅 But the nasal one? So simple. My wife practiced with the trainer last night. We’re both crying a little. This is life-changing. I’m not dying because I was too scared to carry it.

David Cusack

November 23, 2025 AT 07:17 AMIt’s amusing how the ADA mandates glucagon distribution while ignoring the structural failures that make access inequitable. The real issue isn’t patient ignorance-it’s pharmaceutical monopolies and insurance gatekeeping. The fact that Medicaid patients face prior authorization 31% of the time is a moral indictment, not a logistical hiccup.

Elaina Cronin

November 23, 2025 AT 16:41 PMI am absolutely appalled that anyone would hesitate to carry glucagon. This is not a suggestion. It is not optional. It is not a luxury. It is a medical necessity, as essential as an EpiPen for anaphylaxis. If you are on insulin-or sulfonylureas-and you do not have glucagon in your home, in your bag, in your car, you are not managing your condition. You are gambling with your life. And if you are a caregiver and you have not practiced with a trainer device-you are negligent.

Willie Doherty

November 23, 2025 AT 17:45 PMLet’s analyze the data: 59% of at-risk individuals don’t carry glucagon. The cited reason is fear of misuse. But the 2021 study showed only 42% success with the old kit. The new devices-Baqsimi and Gvoke-have 93% efficacy and under-30-second administration. Therefore, the failure rate is not cognitive, it’s systemic. The healthcare system failed to educate, failed to subsidize, failed to normalize. The burden of responsibility is incorrectly placed on the patient.

Cooper Long

November 24, 2025 AT 07:37 AMGlucagon isn’t just for type 1. I’ve seen type 2 patients on insulin get knocked out at work. No one knew what to do. We now have a kit in every break room. Simple. No drama. Just in case. America needs more of this. Not less.

Sheldon Bazinga

November 25, 2025 AT 01:38 AMlol why are we paying for this fancy nasal spray when the old kit still works? Also who the hell has time to train their coworkers? Just slap em and yell ‘ARE U OK?’ and call 911. Also why are they making this so complicated? Its just sugar or insulin right? 😑

Shawn Sakura

November 26, 2025 AT 20:59 PMYou’re not alone. I used to think glucagon was only for ‘bad cases’-until my sister had a seizure at 2am and I fumbled with the old kit for 9 minutes. She’s fine now. But I wish I’d known then what I know now. If you’re reading this and you’re scared? Start small. Watch the 5-minute video. Get the trainer. Practice with your dog if you have to. You’re not weak for being afraid. You’re human. And now you know better. Go get that prescription. I believe in you.

Paula Jane Butterfield

November 28, 2025 AT 15:19 PMMy son’s school nurse refused to give glucagon because she ‘never trained.’ He had a seizure. 911 took 18 minutes. By then his sugar was 32. We had to fight for a 504 plan. Now every teacher in the school has a laminated card with steps. We gave them the trainer device. I cried when they thanked me. This isn’t just medical-it’s human. If you’re a parent, teacher, coworker, friend-don’t wait. Be the person who knows what to do. You could save a life. And if you’re scared? That’s okay. Just do it scared.

Julia Strothers

November 29, 2025 AT 22:02 PMWhy is the FDA pushing glucagon but not banning SGLT2 inhibitors? They cause euglycemic DKA and nobody talks about it. And why are these new devices only available at 12 centers? This is all a cover-up. Big Pharma wants you dependent on their $500 devices while hiding the fact that insulin pricing is what’s really killing people. Glucagon is a bandaid. The real killer? The system. They don’t want you to know that.