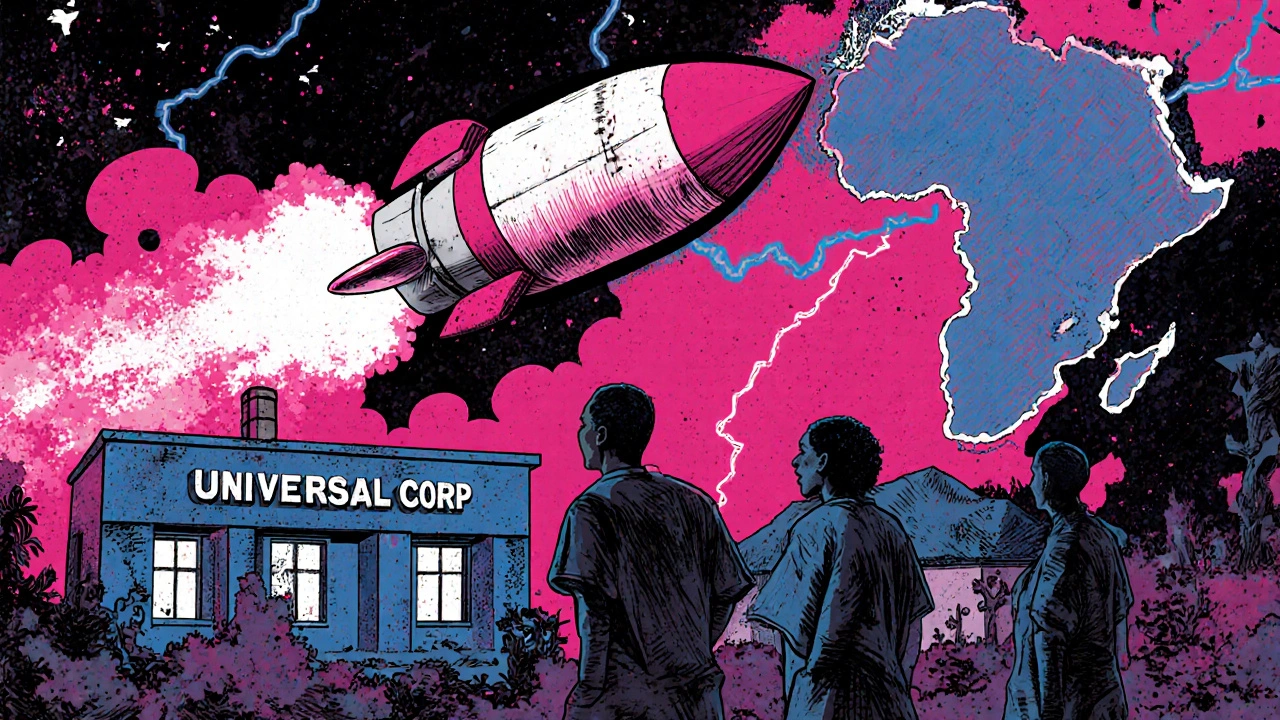

For decades, Africa relied on medicine made halfway across the world to fight HIV. Patients in rural clinics waited months for shipments from India or Europe. When supply chains broke down during the pandemic, people missed doses. Some died because the pills didn’t arrive. That’s changing. On May 6, 2025, something historic happened: the Global Fund bought its first-ever antiretroviral generics made in Africa. The medicine? TLD - a single pill combining tenofovir, lamivudine, and dolutegravir. It was produced by Universal Corporation Ltd in Kenya, the first African company to get WHO prequalification for this first-line HIV treatment. And it was shipped to Mozambique, enough to treat over 72,000 people every year.

Why Local Production Matters

Africa has 17% of the world’s population but bears 65% of all HIV cases. Yet until recently, the continent imported about 80% of its medicines. That’s not just expensive - it’s dangerous. Delays, customs bottlenecks, currency fluctuations, and political instability all threatened treatment continuity. When a country depends on imports, it’s at the mercy of someone else’s logistics, pricing, and priorities.

Now, African manufacturers are stepping in. The TLD pill isn’t just cheaper - it’s better. Dolutegravir, the key ingredient, works faster, has fewer side effects, and stops the virus from becoming resistant more effectively than older drugs. And because it’s made locally, it can be delivered in weeks, not months. Countries like Mozambique, Zambia, and Uganda no longer have to wait for shipments from overseas. They can plan. They can stock. They can treat.

Dr. Ussene Hilário Isse, Mozambique’s Minister of Health, put it plainly: “Africa’s growing capacity to locally produce lifesaving medications marks a strategic shift.” It’s not charity. It’s sovereignty.

How WHO Prequalification Changed Everything

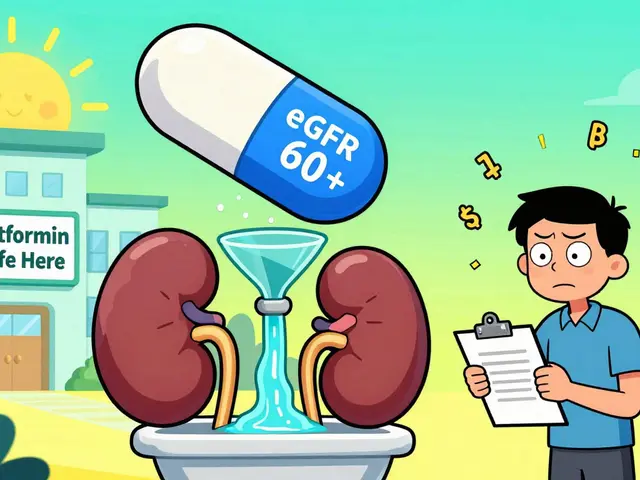

Getting a drug approved in Africa isn’t enough. To be bought by the Global Fund, WHO, or UNICEF, a medicine must pass WHO prequalification. That means meeting the same quality, safety, and effectiveness standards as drugs made in the U.S., EU, or Japan. For years, only Indian and Chinese companies could meet those standards at scale.

Universal Corporation Ltd broke that pattern in 2023. Their factory in Nairobi passed 18 months of inspections - from raw material sourcing to final packaging. Their TLD pill was tested in labs across three continents. The results? Identical to the brand-name version. That’s the key. This isn’t about cutting corners. It’s about building systems that match global benchmarks.

Dr. Meg Doherty of WHO called this “a great milestone towards strengthening supply chain systems in Africa.” It’s not just about pills. It’s about proving African manufacturers can be trusted at the highest level.

From Pills to Diagnostics: Building the Whole System

Getting treatment is only half the battle. You also need to know who has HIV. That’s where diagnostics come in. In July 2025, Codix Bio, a Nigerian company, began producing HIV rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) using technology transferred from SD Biosensor through WHO’s Health Technology Access Programme. These are the same finger-prick tests used in village clinics across rural Malawi and Congo.

Before, these tests were imported. Now, they’re made in Lagos. That means faster restocking, lower costs, and better quality control. When a clinic runs out, they don’t wait for a container from Asia. They order from the next city over.

This isn’t an isolated case. It’s part of a broader push to build end-to-end capacity: testing, treatment, monitoring, and prevention - all within Africa.

The Numbers Behind the Progress

In 2010, 1.3 million people died from AIDS-related causes globally. By 2022, that number dropped to 630,000 - a 52% decline - thanks mostly to wider access to antiretroviral therapy.

In Eastern and Southern Africa, 93% of people living with HIV know their status. 83% are on treatment. 78% have the virus suppressed - meaning they can’t transmit it. That’s progress. But in Western and Central Africa, those numbers are lower: 81%-76%-70%. The gap is real. And local manufacturing is one of the few tools that can close it.

Right now, Africa needs about 15 million person-years of first-line ARV treatment every year. The new Kenyan factory alone can cover 72,000. That’s a start - but not enough. More factories are coming. By Q4 2025, new plants in South Africa, Ethiopia, and Rwanda will begin production. The goal? By 2030, African-made antiretrovirals could supply 20-30% of the continent’s needs.

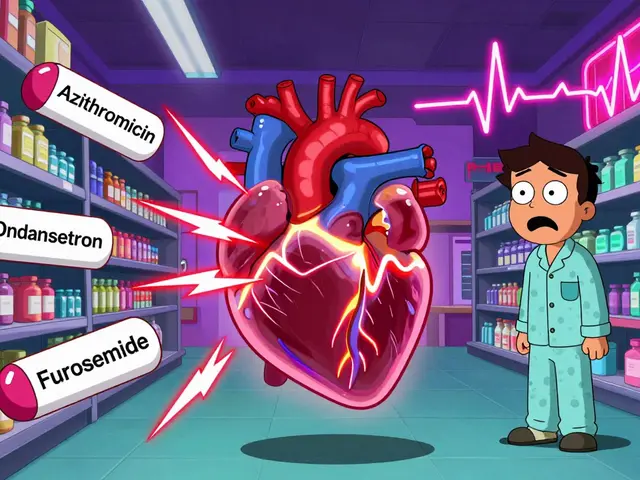

What’s Next? Long-Acting Injections and PrEP

The future of HIV treatment isn’t just pills. It’s injections.

In October 2025, South Africa became the first African country to register a twice-yearly HIV injection called cabotegravir long-acting (CAB LA). No daily pills. Just two shots a year. For people who struggle with adherence, this is life-changing.

Six African companies have licenses from Gilead to make generic versions. Experts say prices could drop 80-90% below the brand. That means millions could afford it. Gilead has also signed agreements with the U.S. State Department and the Global Fund to supply lenacapavir - a new long-acting PrEP drug - at no profit until generics arrive. By the end of 2025, 18 high-burden African countries will be able to start using it.

This isn’t just about treating HIV anymore. It’s about preventing it. And African manufacturers are right in the middle of it.

The Bigger Picture: Health Security and Economic Growth

Building local drug production isn’t just about HIV. It’s about preparing for the next pandemic. When COVID-19 hit, Africa couldn’t make its own vaccines or tests. Now, the same factories making TLD can be retooled to make malaria drugs, TB treatments, or even future vaccines.

The African Union’s Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Plan for Africa (PMPA) wants to raise local production from 2-3% of the continent’s needs to 40% by 2040. That’s ambitious. But it’s possible - if governments invest in regulation, training, and fair pricing.

Right now, African manufacturers are competing with low-cost Indian generics. But they have one advantage: proximity. Faster delivery. Lower shipping costs. Better understanding of local health systems. That’s why the Global Fund and Unitaid are now using “market-shaping” strategies - guaranteeing steady orders so factories can plan, hire, and expand.

Challenges Still Remain

Progress doesn’t mean perfection. Regulatory systems across Africa are still uneven. Some countries lack the staff or labs to inspect factories. Others still favor imported drugs because they’re easier to procure through old channels.

There’s also the issue of funding. African governments can’t pay for all these drugs alone. International donors still play a critical role. But the goal isn’t dependency - it’s transition. The idea is to build industries that can stand on their own.

And then there’s the need for more African-led research. Most HIV drugs were developed based on data from North America and Europe. But HIV strains, co-infections, and patient needs vary across Africa. Local scientists are now calling for “Africanizing research and development” - designing drugs and regimens that match the continent’s reality.

What This Means for People Living with HIV

For a mother in rural Kenya, this means her child won’t miss a dose because a shipment was delayed. For a factory worker in Johannesburg, it means a stable job making medicine for his neighbors. For a clinic nurse in Malawi, it means never having to tell a patient, “We’re out of pills.”

This isn’t just about health. It’s about dignity. It’s about saying: Africa can make its own solutions. And when it does, the whole continent benefits.

Are African-made antiretroviral drugs as effective as imported ones?

Yes. Drugs like TLD made by Universal Corporation Ltd in Kenya have passed WHO prequalification, which requires them to meet the same quality, safety, and effectiveness standards as brand-name drugs from the U.S. or EU. Independent lab tests confirm they work just as well. The difference isn’t in the medicine - it’s in the supply chain.

Why didn’t African countries make these drugs earlier?

For years, patents blocked local production, and there was little investment in manufacturing infrastructure. Many countries lacked strong regulatory systems to meet international standards. Also, international donors often preferred cheaper Indian generics, which created a cycle of dependency. The shift started when African governments, WHO, and donors like the Global Fund began investing in local capacity - not just buying pills, but building factories.

How is this different from Indian generic manufacturers?

Indian manufacturers reduced HIV drug prices from $10,000 per person per year in 2000 to under $100 by 2015 - a huge win. But shipping from India meant delays of 3-6 months. African-made drugs cut delivery time to weeks. They also reduce currency risks, import taxes, and logistical bottlenecks. Plus, local production creates jobs and builds expertise that can be used for other diseases.

Can African countries afford to build more drug factories?

Not alone - but they don’t have to. The Global Fund, Unitaid, the Gates Foundation, and CIFF are funding factory builds and providing guaranteed purchase agreements. This reduces financial risk for manufacturers. The goal isn’t for every country to build its own factory - but for regional hubs to serve multiple nations, like the one in Kenya supplying Mozambique, Zambia, and beyond.

What about long-acting HIV treatments? Will they be available in Africa?

Yes. South Africa already registered the twice-yearly injection cabotegravir long-acting in October 2025. Six African companies have licenses to make generic versions, and prices are expected to drop by 80-90%. Gilead is also supplying lenacapavir for PrEP at no profit until generics are ready. The first low-income countries will get it before the end of 2025.

Is this just about HIV, or does it help with other diseases too?

It’s about more than HIV. The same factories making ARVs can be adapted to produce malaria drugs, TB treatments, or even future vaccines. The regulatory systems, trained workers, and supply chains being built now will help Africa respond to any future health crisis - not just one disease, but many.

Comments

Ryan Anderson

November 15, 2025 AT 05:45 AMThis is honestly one of the most hopeful things I’ve seen in global health in years 🙌 Africa building its own solutions? Yes please. No more waiting for someone else to decide when we get medicine. Dolutegravir is a game-changer, and seeing it made right where it’s needed? That’s sovereignty in action.

Eleanora Keene

November 15, 2025 AT 21:54 PMI just want to say how proud I am of the African scientists and workers behind this. It’s not just about pills-it’s about dignity, jobs, and long-term resilience. The fact that WHO prequalification was met? That’s not luck. That’s excellence. 🌍❤️

Joe Goodrow

November 16, 2025 AT 21:50 PMSo now we’re supposed to trust African factories more than Indian ones? Please. India’s been making cheap, reliable generics for decades. This feels like feel-good propaganda with no real cost analysis. Who’s paying for all these factories? US taxpayers?

Don Ablett

November 18, 2025 AT 15:27 PMThe WHO prequalification process is rigorous and non-negotiable. The fact that Universal Corporation passed it after 18 months of audits speaks to institutional discipline. This is not symbolic. It is systemic. The implications for regional health architecture are profound. Further analysis is warranted.

Kevin Wagner

November 20, 2025 AT 13:02 PMLet’s be real-this is the most badass thing to happen in global health since PrEP went mainstream. African labs outperforming Big Pharma? Check. Local jobs? Check. No more 6-month delays killing people? DOUBLE CHECK. This isn’t charity. This is a revolution with pills. Let’s fund the next 10 factories and stop talking.

gent wood

November 21, 2025 AT 00:17 AMThis development is profoundly significant, and I believe it represents a turning point in global health equity. The reduction in supply chain vulnerability alone justifies the investment. The fact that diagnostic tools are now being produced locally as well indicates a holistic approach to health security. This is not merely incremental progress; it is foundational.

Dilip Patel

November 22, 2025 AT 05:38 AMIndia made these drugs cheap for 20 years and now Africa wants to copy? You think a factory in Nairobi can match the scale of Hyderabad? Ha. This is just a political stunt. WHO prequalification? Everyone knows they bend rules for political reasons. And who’s gonna pay for the extra cost? You? Me? India still wins.

Jane Johnson

November 23, 2025 AT 12:48 PMBut is this sustainable? Who will regulate these factories in 10 years? What happens when donor funding dries up? Are we creating dependency under a new name?

Sean Hwang

November 24, 2025 AT 20:20 PMMy cousin works at a clinic in Malawi. She told me they used to get pills 3 months late. Now they order from Kenya and get them in 10 days. No more crying patients. Just pills. Simple. That’s all that matters.

Barry Sanders

November 26, 2025 AT 01:43 AMSo now we’re glorifying African pharma like it’s some miracle? The quality control is still sketchy. And don’t even get me started on the power grabs by local elites who’ll control distribution. This isn’t progress-it’s a new colonialism with better PR.

Chris Ashley

November 26, 2025 AT 06:15 AMbro this is wild imagine your kid gets meds because a factory 500 miles away made it instead of some warehouse in india. no shipping delays. no customs. just pills. that’s the future.

kshitij pandey

November 27, 2025 AT 11:44 AMAs someone from India, I’m so proud of what our generics did for Africa. But now seeing African factories rise? That’s the next chapter. This isn’t competition-it’s collaboration. India taught them the price game. Now Africa is teaching us about speed, trust, and local ownership. We should cheer this on.

Brittany C

November 27, 2025 AT 21:24 PMThe integration of diagnostics with therapeutic production represents a systems-level paradigm shift in public health infrastructure. The convergence of point-of-care testing with locally manufactured ARVs enables true treatment-as-prevention cascades, particularly in low-resource settings with fragmented logistics.

Sean Evans

November 28, 2025 AT 17:55 PMLook, I’m all for African empowerment, but let’s not ignore the elephant in the room: most of this is funded by Western donors. So who’s really in control? The Global Fund? The Gates Foundation? This isn’t independence-it’s a rebranding of dependency with African logos on the bottles. 🤡