Air Pollution Impact Calculator

Your COPD Risk Assessment

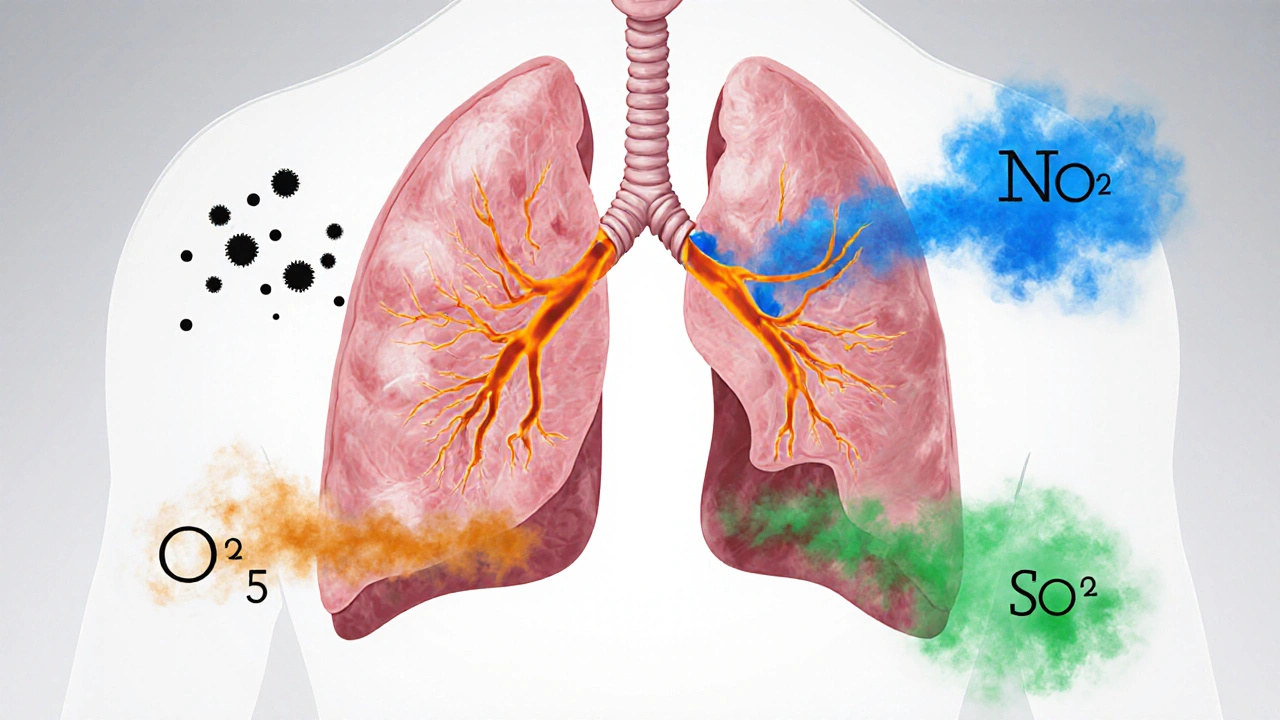

Key Pollutants & Their Effects

PM2.5

Fine particles causing deep lung inflammation

Low RiskNO₂

Traffic-related irritant causing bronchial issues

Moderate RiskO₃

Photochemical oxidant increasing exacerbation risk

High RiskSO₂

Acute bronchoconstrictor with long-term effects

Moderate RiskEvery year the World Health Organization links more than air pollution to over 4million premature deaths - and a big chunk of those deaths are caused by obstructive lung disease.

What is Obstructive Pulmonary Disease?

COPD is a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease marked by persistent airflow limitation and progressive breathlessness. It includes chronic bronchitis and emphysema and is diagnosed with spirometry, where the forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) falls below 80% of the predicted value. While smoking remains the top cause, ambient air quality has emerged as a silent driver, especially in urban settings.

Key Pollutants that Harm the Lungs

Not all air pollutants act the same. The most damaging for COPD are:

- Particulate Matter (PM2.5) - tiny particles smaller than 2.5µm that lodge deep in the bronchioles.

- Nitrogen Dioxide (NO₂) - produced by traffic engines and fossil‑fuel power plants.

- Ozone (O₃) - a secondary pollutant formed when sunlight reacts with NO₂ and volatile organic compounds.

- Sulphur Dioxide (SO₂) - emitted from coal combustion and heavy industry.

How Pollutants Trigger COPD

Scientists have mapped three main pathways:

- Inflammation: Inhaled particles activate alveolar macrophages, releasing cytokines that inflame airway walls.

- Oxidative stress: Reactive oxygen species from pollutants damage epithelial cells, accelerating lung tissue loss.

- Airway remodeling: Chronic irritation leads to thickening of the bronchial wall and loss of elastic recoil, making exhalation harder.

A 2022 Lancet meta‑analysis found that each 10µg/m³ rise in average annual PM2.5 exposure increased COPD incidence by roughly 8% and accelerated the decline in FEV1 by 12mL per year.

Who Is Most at Risk?

Risk isn’t uniform. The following groups feel the impact the hardest:

- Adults over 65 - age‑related loss of lung elasticity compounds pollutant damage.

- Current or former smokers - tobacco smoke primes the immune system, so pollutants act like a second hit.

- People with pre‑existing asthma - airway hyper‑responsiveness makes them more susceptible to ozone spikes.

- Residents of high‑traffic corridors - living within 500m of a major road can raise personal PM2.5 exposure by up to 30%.

Seeing the Numbers: A Quick Comparison

| Pollutant | Common Sources | Typical Urban Concentration (µg/m³) |

Key COPD Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| PM2.5 | Vehicle exhaust, wood burning, industry | 12-35 | Deep‑lung inflammation, accelerated FEV1 decline |

| NO₂ | Traffic emissions, diesel generators | 30-60 | Bronchial irritation, increased mucus production |

| O₃ | Photochemical reaction of NO₂ + VOCs | 50-100 (peak summer) | Airway hyper‑responsiveness, exacerbation risk |

| SO₂ | Coal plants, heavy industry | 5-20 | Acute bronchoconstriction, long‑term remodeling |

Practical Steps to Reduce Personal Exposure

Even if you can’t change city‑wide emissions overnight, you can protect yourself:

- Check the local Air Quality Index (AQI) on your phone. If it’s above 100, limit outdoor activity, especially vigorous exercise.

- When walking or cycling near traffic, stay on the side away from the road and keep windows closed.

- Invest in a high‑efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter for your bedroom. Studies in the UK show a 25% drop in indoor PM2.5 after 2weeks of use.

- Wear a certified N95 or FFP2 mask on high‑pollution days. Proper fit cuts particle penetration by up to 95%.

- Plants such as spider plant, peace lily, or Boston fern can modestly lower indoor VOC levels, complementing mechanical filtration.

Policy Moves That Matter

Individual action pairs with community‑level change. The UK’s Clean Air Strategy (2021) set a target of cutting PM2.5 levels to 10µg/m³ by 2030. Cities like Bristol have introduced “clean‑air zones” where the most polluting diesel buses are banned. Supporting such initiatives-by voting, joining local advocacy groups, or simply sharing data-helps lower the baseline exposure for everyone.

When to Seek Medical Help

If you notice any of these warning signs, book a review with your GP:

- Persistent coughing that produces mucus for more than three months.

- Shortness of breath during everyday tasks like climbing stairs.

- Frequent respiratory infections or flare‑ups after high‑pollution days.

Early spirometry can catch COPD before severe damage occurs, and lifestyle changes (smoking cessation, inhaler therapy, pulmonary rehab) can slow progression.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can short‑term exposure to smog trigger COPD?

Acute spikes can aggravate existing airway inflammation and cause a flare‑up, but a diagnosis of COPD requires long‑term exposure and persistent airflow limitation.

Is indoor air quality as bad as outdoor air?

Indoor levels often mirror outdoor concentrations, especially in poorly sealed homes. Cooking, heating, and smoking indoors can push PM2.5 even higher, so ventilation and filtration matter.

Do masks really work against fine particles?

Yes, when they meet N95/FFP2 standards and fit snugly. They filter at least 95% of particles down to 0.3µm, covering the size range of harmful PM2.5.

How long does it take for lung function to improve after moving to cleaner air?

Research from the European Respiratory Journal shows measurable FEV1 gains within 6-12months of relocating to an area with PM2.5 levels under 10µg/m³, especially when combined with smoking cessation.

What role does genetics play compared to pollution?

Genetics account for roughly 20-30% of COPD susceptibility. Pollution can act as the environmental trigger that pushes a genetically predisposed person over the clinical threshold.

Comments

Anna Graf

October 4, 2025 AT 01:41 AMWe often think of air as something we simply breathe, but it is also a carrier of invisible particles that shape our health. When the city smog thickens, those tiny particles slip deep into the bronchioles and start a slow fire in our lungs. The link between chronic exposure and obstructive disease feels almost inevitable, like a quiet river eroding a stone over time. Simple steps, like checking the AQI and using filters, can soften that erosion.

Jarrod Benson

October 9, 2025 AT 12:59 PMWow, this article really blows the lid off how everyday air can become a silent enemy to our lungs, and I’m pumped to share a few extra thoughts that might help everybody take control. First off, remember that the numbers on your phone aren’t just abstract figures-they translate into real particles that invade the deepest parts of your respiratory system. When you live near a busy road, the constant stream of exhaust pushes PM2.5 right into your alveoli, and over years that adds up like paying tiny interest that becomes a huge debt. The statistics from the 2022 Lancet study are staggering; a ten microgram per cubic meter rise in PM2.5 adds roughly an eight percent jump in COPD cases, which is a massive public health alarm. If you’re a smoker or former smoker, those particles act like a second gun on the same target, compounding the damage beyond what either would do alone. Age is another silent partner-people over sixty‑five have less elastic tissue, so the same pollutant load hits them harder and speeds up the decline in FEV1. One practical tip: set up alerts on a reliable AQI app so you get a heads‑up before you head out for a run or a bike ride. On high‑pollution days, swap the outdoor jog for an indoor treadmill session, but make sure the room has a HEPA filter humming quietly in the background. Investing in a good N95 mask isn’t just for construction sites; a properly fitted one can filter out over ninety‑five percent of those nasty PM2.5 particles. If you can’t afford a brand‑new purifier, consider DIY options like a box fan fitted with a furnace filter-studies have shown they can cut indoor particulate levels by a respectable margin. Don’t forget ventilation; opening windows during a clean‑air window can flush out indoor pollutants that build up from cooking or cleaning. Community action matters too-join or start a neighborhood “clean‑air” group that pushes for greener traffic policies or tree planting initiatives. It may sound like a lot, but each small habit adds up like bricks building a barrier against the invisible assault. Finally, stay on top of your health checks; annual spirometry can catch early signs before they become irreversible, and early intervention can preserve lung function for years. So, gear up, stay informed, and keep those lungs breathing easy!

Liz .

October 15, 2025 AT 00:17 AMair quality is a global issue we all share it affects kids in Delhi and seniors in Detroit so staying aware of local smog levels is a simple act of solidarity

tom tatomi

October 20, 2025 AT 11:34 AMThe calculator’s scoring system feels a bit arbitrary, ignoring personal susceptibility factors such as genetics, so I’m not convinced the risk categories fully capture an individual’s true danger.

Tom Haymes

October 25, 2025 AT 22:52 PMThink of the recommendations as a training plan for your lungs: start with small, consistent changes like checking the AQI each morning, then gradually add stronger steps such as using a HEPA filter and incorporating regular breathing exercises to strengthen airway resilience.

Scott Kohler

October 31, 2025 AT 09:10 AMOne might wonder whether the “air quality alerts” are merely a sophisticated distraction, designed by big‑energy conglomerates to keep the public complacent while they quietly pump more sulphur into the atmosphere under the guise of “economic growth.”

Brittany McGuigan

November 5, 2025 AT 20:27 PMSurely the goverment would never allow such a plot, but the evidnce of loosing air standards in many citiies suggests otherwise, especially when they claim to be pro‑environment while actual measurments keep riseing.

Priya Vadivel

November 11, 2025 AT 07:45 AMIt’s truly heartbreaking, how millions of families, often those already vulnerable, are forced to breathe compromised air, yet we have the tools-air filters, masks, community advocacy-to mitigate this crisis, and every small effort, no matter how modest, contributes to a healthier future for our children.

Dharmraj Kevat

November 16, 2025 AT 19:03 PMWhen the smog rolls in it feels like the sky itself is choking, and only the bravest dare to step outside without armor.

Lindy Fujimoto

November 22, 2025 AT 06:20 AMHonestly, you’re all ignoring the biggest truth 😒-the only way to truly protect yourself is to demand policy change, not just buy a mask. 🌍🚫

darren coen

November 27, 2025 AT 17:38 PMThis is solid info.

Jennifer Boyd

December 3, 2025 AT 04:56 AMAbsolutely! Let’s keep sharing these tips and cheering each other on, because together we can breathe easier and stay hopeful! 🌟

Lauren DiSabato

December 8, 2025 AT 16:13 PMWhile the article covers the basics, it neglects to mention that recent CRISPR‑based gene editing trials hint at future therapeutic avenues that could directly counteract pollutant‑induced epigenetic changes in lung tissue.

kristine ayroso

December 14, 2025 AT 03:31 AMGreat points! Just remember, a simple habit like closing windows during rush hour + using a cheap box‑fan filter can make a huge diffrence – every lil effort counts.

Ben Small

December 19, 2025 AT 14:49 PMDon’t sit on the couch waiting for the government-grab a filter, suit up with an N95, and take charge of your own air right now!

Chidi Anslem

December 25, 2025 AT 02:06 AMAir quality is a shared responsibility; when we cleanse our immediate environment, we also contribute to a collective atmosphere that benefits the whole community, echoing the principle that the well‑being of one is intertwined with the well‑being of all.

Holly Hayes

December 30, 2025 AT 13:24 PMpeople should stop ignorng the science and start actin like adults.

Penn Shade

January 5, 2026 AT 00:41 AMIf you’re still doubting the link between particulate matter and COPD after reading the data, you’re simply overlooking a fundamental public‑health truth taught in any reputable medical curriculum.